- The 20th iteration of Bitcoin Core, the open source software powering the Bitcoin blockchain, was released Wednesday.

- Experimental software called “Asmap” was included to protect against a theoretical “Erebus” attack.

- An Erebus attack allows nation-states and/or large internet providers such as Amazon Web Services to spy, double-spend or censor bitcoin transactions.

- The patch would help thwart an attack but is not a conclusive fix.

Bitcoin Core released a new software update Wednesday, Bitcoin Core 0.20.0. Notably, the release includes experimental software to hedge against attacks from players the size of nation-states, which could effectively fracture the Bitcoin network.

Called “Asmap,” this new configuration protects the peer-to-peer architecture of bitcoin nodes by mapping connections to Tier 1 or larger Tier 2 Autonomous Systems (AS) – internet operators capable of connecting to multiple networks with defined routing plans such as Amazon Web Services or states – and then “limiting the connections made to any single [AS].”

In essence, the so-called “Erebus” attack allows an AS to censor large swaths of the Bitcoin network by limiting and then spoofing peer-to-peer (P2P) connections. Failure to address the flaw could lead to highly undesirable consequences for Bitcoin such as a major mining pool or exchange being cut off from the rest of the network.

An Erebus attack was first hypothesized by researchers at the National University of Singapore (NUS) – Muoi Tran, Inho Choi, Gi Jun Moon, Anh V. Vu and Min Suk Kang – who co-authored a 2019 paper detailing the attack.

The kicker? It’s entirely undetectable until too late.

Attack architecture

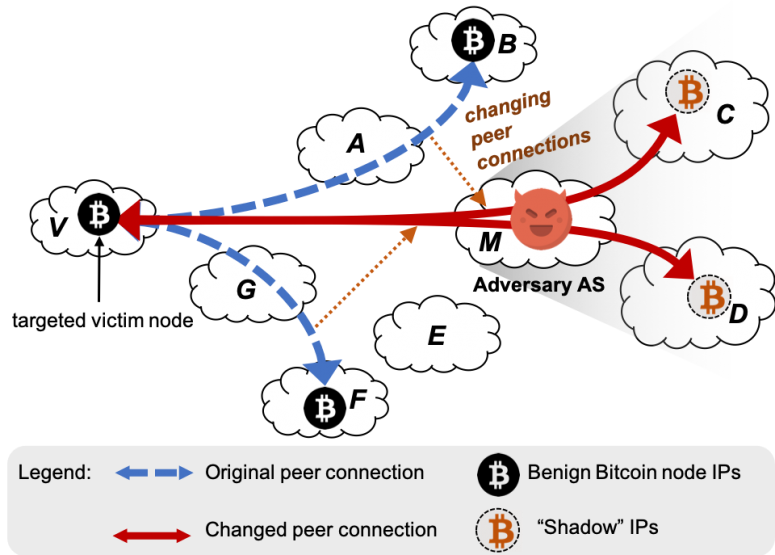

Erebus falls under the general “man-in-middle” attack scheme made possible through the P2P nature of bitcoin. Greek for “shadow,” Erebus is itself a derivative of the “Eclipse” attack first described in 2015.

As theorized, the malicious actor will try and connect to as many nodes as possible around one node that the attacker wishes to isolate (an exchange’s node, for example). The malicious node can begin to influence the victim node by connecting to its peers. The end goal is to make the victim node’s eight external connections pass through the malicious party.

Once accomplished, the victim is isolated from the rest of the network. The malicious actor can decide what transactions and information are sent to the victim; this information can be completely different from the rest of the network and could even lead to a chain split or censorship.

Erebus attack schematic. Source: National University of Singapore

Erebus attack schematic. Source: National University of Singapore

“Our attack is feasible not because of any newly discovered bugs in the Bitcoin core implementation but the fundamental topological advantage of being a network adversary,” the NUS academics wrote in 2019. “That is, our EREBUS adversary AS, as a stable man-in-the-middle network, can utilize a large number of network addresses reliably over an extended period of time. Moreover, an AS can target specific nodes such as mining pools or crypto exchanges.”

If an exchange or mining pool’s node was shadow attacked, an AS could effectively cut off the entity from connecting to the network. An Erebus styled attack would be even more devastating given the bitcoin mining industry’s continued centralization into mining pools.

For bitcoin, 10,000 nodes are currently susceptible, with the academics estimating a five- to six-week attack period needed to successfully pull off the stunt. Bitcoin has a lower bound of 11,000 listening nodes with an upper bound 100,000 non-listening or “private” nodes, according to bitcoin core contributor Luke Dashjr.

As of Wednesday, a solution to the attack is now embedded in the 20th edition of Bitcoin’s code, making the fledgling monetary system even more censorship-resistant.

Erebus and the internet

The Erebus attack is in no way the fault of Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous creator of bitcoin. It’s just how the internet evolved.

“We are solving a problem of not your internet provider, but some internet provider in the world screwing you because that’s much more dangerous,” said Chaincode Labs researcher and Bitcoin Core contributor Gleb Naumenko.

Like a hub and spoke, nation-states and large ISPs control access to the internet. Networks further break down into individual IP addresses like the phone you’re probably reading this on.

Bitcoin nodes operate in the same manner with each node having its own IP address, unless hidden via Tor or another obfuscation method. Once a node decides to go through the malicious node, the AS can decide how that node connects to the rest of the network for that particular connection.

When a bitcoin node connects to the network, it typically makes eight outbound connections meaning it will broadcast a transaction to eight other bitcoin nodes. Slowly but surely, every node in the Bitcoin network confirms and writes down a transaction made by another node, if valid. In Erebus, if the AS is successful in grabbing all of eight of the node’s external connections, the node serves at the whim of the AS.

The attack comes in two parts: reconnaissance and execution.

First, the AS maps out IP addresses of nodes within the network, noting where they can be found and what peers they connect to. Then the AS slowly begins to influence the peers it has surveyed. In other words, the malicious actor is working to exclusively accept connections from as many nodes in their community as possible.

The number of connections depends on the attacker’s motivations: censoring individual transactions, blocking off-chain transactions (such as on the Lightning Network) from occurring, selfishly mining a split chain of the network to get a larger percentage of block rewards or even launching a 51 percent attack to double-spend bitcoins.

The more nodes a malicious attacker exclusively controls, the more damage they can do to the network. In fact, with enough connections, they can effectively shut down bitcoin by controlling large swaths of the bitcoin network, said the NUS team.

“A powerful adversary, such as a nation-state attacker, may even aim to disrupt a large portion of the underlying peer-to-peer network of a cryptocurrency. At a small scale, the adversary can arbitrarily censor the transactions from the victim,” the academics write.

Stealth mode

Unlike the Eclipse attack, Erebus is stealth.

“So the difference is, what they are doing is it’s not detectable – there really is no evidence. It looks like regular behavior,” Naumenko said about an AS fomenting the attack.

The internet is made up of different data levels. Some layers reveal information, some don’t and some contain too much information to keep track of.

In Eclipse, an attacker uses information from the internet protocol layer while Erebus uses information on the bitcoin protocol layer. Eclipse’s route “immediately reveals” the identity of the attacker, the academics said. Conversely, Erebus does not, making it impossible to detect until an attack is underway.

While the threat remains alive as long as the current internet stack exists as it does, there remain options for thwarting a would-be attacker. Wednesday’s Updates were led by Blockstream co-founder and engineer Pieter Wuille and Chaincode’s Naumenko.

The fix? A Zelda-esque mini-map of the different nation-states and ISPs typical internet routing paths. Nodes can then choose peer connections based on the map with the intention of connecting to multiple bodies rather than one AS.

The solution from the Bitcoin Core team makes the attack unlikely by adding further obstacles to isolating nodes from the rest of the network, but may not provide a permanent fix.

“This option is experimental and subject to removal or breaking changes in future releases,” Bitcoin Core contributor Wladimir J. van der Laan said Wednesday in a developer’s email.

Naumenko said they decided to tackle the issue due to its clear danger to the network. The attack was also novel, spiking his personal interest.

It’s not just bitcoin, though. As Naumenko noted, almost all cryptos are threatened by an Erebus attack. The NUS paper itself cites dash (DASH), litecoin (LTC) and zcash (ZEC) as examples of other coins at risk of similar attacks.

“It’s a fundamental problem and the protocols are very similar. It’s systemic. It’s not some bug where you forgot to update the variable,” Chaincode’s Naumenko said. “It’s peer-to-peer architecture and [part of] all the systems.”

Disclosure

The leader in blockchain news, CoinDesk is a media outlet that strives for the highest journalistic standards and abides by a strict set of editorial policies. CoinDesk is an independent operating subsidiary of Digital Currency Group, which invests in cryptocurrencies and blockchain startups.

Source